The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass

page

(Pre-Tridentine Roman Missals and Traditions)

Source: New Advent

Note: Only the references to the source material have been

removed from the text used on New Advent for easier reading.

When a name is mentioned below, it usually referred to

a scholar of the time the 1909 Catholic Encyclopedia

was written.

It should be noted that the name Mass (missa)

applies to the Eucharistic service in the Latin rites

only. Neither in Latin nor in Greek has it ever been

applied to any Eastern rite. For them the corresponding

word is Liturgy (liturgia). It is a mistake that leads

to confusion, and a scientific inexactitude, to speak

of any Eastern Liturgy as a Mass.

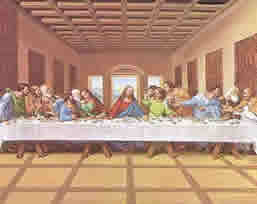

As stated on the

main Holy Mass page the Western Mass, like all

liturgies, begins, of course, with the Last Supper.

What Christ then did, repeated as he commanded in memory

of Him, is the nucleus of the Mass. Many scholars believe

that when Christ instituted the Last Supper, he did

so in Aramaic.

As soon as the Faith was brought to the West the Holy Eucharist

was celebrated here, as in the East. At first the language

used was Greek. Out

of that earliest Liturgy, the language being changed to

Latin,

developed the two great parent rites of the West, the Roman

and the Gallican. It should be noted the question of the

change of language from Greek to Latin is less important

than if might seem. It came about naturally when Greek

ceased to be the usual language of the Roman Christians.

Of these two the Gallican Mass may be

traced without difficulty. It is so plainly Antiochene

in its structure, in the very text of many of its prayers,

that we are safe in accounting for it as a translated form

of the Liturgy of Jerusalem-Antioch, brought to the West

at about the time when the more or less fluid universal

Liturgy of the first three centuries gave place to different

fixed rites.

Justin Martyr, Clement of Rome, Hippolytus (d. 235), and

Novatian (c. 250) all agree in the Liturgies they describe,

though the evidence of the last two is scanty.

Justin gives us the fullest Liturgical

description of any Father of the first three centuries

(Apol. I, lxv, lxvi.). He describes how the Holy Eucharist

was celebrated at Rome in the middle of the second century;

his account is the necessary point of departure, one

end of a chain whose intermediate links are hidden. We

have hardly any knowledge at all of what developments

the Roman Rite went through during the third and fourth

centuries. This is the mysterious time where conjecture

may, and does, run riot. By the fifth century we come

back to comparatively firm ground, after a radical change.

At this time we have the fragment in Pseudo-Ambrose, "De

Sacramentis" (about

400. Cf. P.L., XVI, 443), and the letter of Pope Innocent

I (401-17) to Decentius of Eugubium (P.L., XX, 553). In

these documents we see that the Roman Liturgy is said in

Latin and has already become in essence the rite we still

use. A few indications of the end of the fourth century

agree with this. A little later we come to the earliest

Sacramentaries (Leonine, fifth or sixth century; Gelasian,

sixth or seventh century) and from then the history of

the Roman Mass is fairly clear. The fifth and sixth centuries

therefore show us the other end of the chain. For the interval

between the second and fifth centuries, during which the

great change took place, although we know so little about

Rome itself, we have valuable data from Africa. There is

every reason to believe that in liturgical matters the

Church of Africa followed Rome closely. We can supply much

of what we wish to know about Rome from the African Fathers

of the third century, Tertullian (d. c. 220), St. Cyprian

(d. 258), the Acts of St. Perpetua and St. Felicitas (203),

St. Augustine (d. 430).

The question of the change of language

from Greek to Latin is less important than if might seem.

It came about naturally when Greek ceased to be the usual

language of the Roman Christians. Pope Victor I (190-202),

an African, seems to have been the first to use Latin

at Rome, Novatian writes Latin. By the second half of

the third century the usual liturgical language at Rome

seems to have been Latin, though fragments of Greek remained

for many centuries. Other writers think that Latin was

not finally adopted till the end of the fourth century.

No doubt, for a time both languages were used. The Creed

was sometimes said in Greek, some psalms were sung in

that language, the lessons on Holy Saturday were read

in Greek and Latin as late as the eighth century. There

are still such fragments of Greek ("Kyrie

eleison", "Agios O Theos") in the Roman

Mass. But a change of language does not involve a change

of rite. Novatian's Latin allusions to the Eucharistic

prayer agree very well with those of Clement of Rome in

Greek, and with the Greek forms in Apostolic Constitutions,

VIII.

NOTE: The Apostolic Constitutions were

a fourth-century pseudo-Apostolic collection, in eight

books, of independent, though closely related, treatises

on Christian discipline, worship, and doctrine, intended

to serve as a manual of guidance for the clergy, and to

some extent for the laity.

The Africans, Tertullian, St. Cyprian,

etc., who write Latin, describe a rite very closely related

to that of Justin and the Apostolic Constitutions. The

Gallican Rite, as in Germanus of Paris, shows how Eastern

-- how "Greek" --

a Latin Liturgy can be. We must then conceive the change

of language in the third century as a detail that did not

much affect the development of the rite. No doubt the use

of Latin was a factor in the Roman tendency to shorten

the prayers, leave out whatever seemed redundant in formulas,

and abridge the whole service. Latin is naturally terse,

compared with the rhetorical abundance of Greek. This difference

is one of the most obvious distinctions between the Roman

and the Eastern Rites.

If we may suppose that during the

first three centuries there was a common Liturgy throughout

Christendom, variable, no doubt, in details, but uniform

in all its main points, which common Liturgy is represented

by that of the eighth book of the Apostolic Constitutions,

we have in that the origin of the Roman Mass as of all

other liturgies. There are, indeed, special reasons for

supposing that this type of liturgy was used at Rome.

The chief authorities for it (Clement, Justin, Hippolytus,

Novatian) are all Roman. Moreover, even the present Roman

Rite, in spite of later modifications, retains certain

elements that resemble those of the Apost. Const. Liturgy

remarkably.

Between this original Roman Rite

(which we can study only in the Apost. Const.) and the

Mass as it emerges in the first sacramentaries (sixth

to seventh century) there is a great change. Much of

this change is accounted for by the Roman tendency to

shorten. The Apost, Const. has five lessons; Rome has

generally only two or three. At Rome the prayers of the

faithful after the expulsion of the catechumens and the

Intercession at the end of the Canon have gone. Both

no doubt were considered superfluous since there is a

series of petitions of the same nature in the Canon.

But both have left traces. We still say Oremus before

the Offertory, where the prayers of the faithful once stood,

and still have these prayers on Good Friday in the collects.

And the "Hanc Igitur" is a fragment of the Intercession.

The first great change that separates Rome from all the

Eastern rites is the influence of the ecclesiastical year.

The Eastern liturgies remain always the same except for

the lessons, Prokeimenon (Gradual-verse), and one or two

other slight modifications. On the other hand the Roman

Mass is profoundly affected throughout by the season or

feast on which it is said. Probst's theory was that this

change was made by Pope Damasus. This idea is now abandoned.

Indeed, we have the authority of Pope Vigilius (540-55)

for the fact that in the sixth century the order of the

Mass was still hardly affected by the calendar. The influence

of the ecclesiastical year must have been gradual. The

lessons were of course always varied, and a growing tendency

to refer to the feast or season in the prayers, Preface,

and even in the Canon, brought about the present state

of things, already in full force in the Leonine Sacramentary.

That Damasus was one of the popes who modified the old

rite seems, however, certain. St. Gregory I (590-604) says

he introduced the use of the Hebrew Alleluia from Jerusalem.

It was under Damasus that the Vulgate became the official

Roman version of the Bible used in the Liturgy; a constant

tradition ascribes to Damasus' friend St. Jerome (d. 420)

the arrangement of the Roman Lectionary. Mgr Duchesne thinks

that the Canon was arranged by this pope (Origines du Culte,

168-9). A curious error of a Roman theologian of Damasus'

time, who identified Melchisedech with the Holy Ghost,

incidentally shows us one prayer of our Mass as existing

then, namely the "Supra quæ" with its allusion

to "summus sacerdos tuus Melchisedech".

The Mass from the Fifth to the Seventh

Century

By about the fifth century we begin

to see more clearly. Two documents of this time give

us fairly large fragments of the Roman Mass. Innocent

I (401-17), in his letter to Decentius of Eugubium, alludes

to many features of the Mass. We notice that these important

changes have already been made: the kiss of peace has

been moved from the beginning of the Mass of the Faithful

to after the Consecration, the Commemoration of the Living

and Dead is made in the Canon, and there are no longer

prayers of the faithful before the Offertory. Rietschel

thinks that the Invocation of the Holy Ghost has already

disappeared from the Mass. Innocent does not mention

it, but we have evidence of it at a later date under

Gelasius I. Rietschel (loc. cit.) also thinks that there

was a dogmatic reason for these changes, to emphasize

the sacrificial idea. We notice especially that in Innocent's

time the Prayer of Intercession follows the Consecration.

The author of the treatise "De Sacramentis" says

that he will explain the Roman Use, and proceeds to quote

a great part of the Canon. From this document we can reconstruct

the following scheme: The Mass of the Catechumens is still

distinct from that of the faithful, at least in theory.

The people sing "Introibo ad altare Dei" as the

celebrant and his ministers approach the altar (the Introit).

Then follow lessons from Scripture, chants (Graduals),

and a sermon (the Catechumens Mass). The people still make

the Offertory of bread and wine. The Preface and Sanctus

follow, then the prayer of Intercession and the Consecration

by the words of Institution. From this point the text of

the Canon is quoted. Then come the Anamnesis, joined to

it the prayer of oblation, i.e. practically our "Supra

quæ" prayer, and the Communion with the form: "Corpus

Christi, R. Amen", during which Ps. xxii is sung.

At the end the Lord's Prayer is said.

In the "De Sacramentis" then, the Intercession

comes before the Consecration, whereas in Innocent's letter

it came after. This transposition should be noted as one

of the most important features in the development of the

Mass. The "Liber Pontificalis" contains a number

of statements about changes in and additions to the Mass

made by various popes, as for instance that Leo I (440-61)

added the words "sanctum sacrificium, immaculatam

hostiam" to the prayer "Supra quæ",

that Sergius I (687-701) introduced the Agnus Dei, and

so on. These must be received with caution; the whole book

still needs critical examination. In the case of the Agnus

Dei the statement is made doubtful by the fact that it

is found in the Gregorian Sacramentary (whose date, however,

is again doubtful). A constant tradition ascribes some

great influence on the Mass to Gelasius I (492-6). Gennadius

says he composed a sacramentary; the Liber Pontificalis

speaks of his liturgical work, and there must be some basis

for the way in which his name is attached to the famous

Gelasian Sacramentary. What exactly Gelasius did is less

easy to determine.

We come now to the end of a period

at the reign of St. Gregory I (590-604). Gregory knew

the Mass practically as we still have it. There have

been additions and changes since his time, but none to

compare with the complete recasting of the Canon that

took place before him. At least as far as the Canon is

concerned, Gregory may be considered as having put the

last touches to it. His biographer, John the Deacon,

says that he "collected the Sacramentary

of Gelasius in one book, leaving out much, changing little,

adding something for the exposition of the Gospels" (Vita

S. Greg., II, xvii). He moved the Our Father from the end

of the Mass to before the Communion, as he says in his

letter to John of Syracuse: "We say the Lord's Prayer

immediately after the Canon [max post precem] . . . It

seems to me very unsuitable that we should say the Canon

which an unknown scholar composed over the oblation and

that we should not say the prayer handed down by our Redeemer

himself over His body and blood". He is also credited

with the addition: "diesque nostros etc." to

the "Hanc igitur". Benedict XIV says that "no

pope has added to, or changed the Canon since St. Gregory".

There has been an important change since, the partial amalgamation

of the old Roman Rite with Gallican features; but this

hardly affects the Canon. We may say safely that a modern

Latin Catholic who could be carried back to Rome in the

early seventh century would -- while missing some features

to which he is accustomed -- find himself on the whole

quite at home with the service he saw there.

This brings us back to the most difficult question: Why

and when was the Roman Liturgy changed from what we see

in Justin Martyr to that of Gregory I? The change is radical,

especially as regards the most important element of the

Mass, the Canon. The modifications in the earlier part,

the smaller number of lessons, the omission of the prayers

for and expulsion of the catechumens, of the prayers of

the faithful before the Offertory and so on, may be accounted

for easily as a result of the characteristic Roman tendency

to shorten the service and leave out what had become superfluous.

The influence of the calendar has already been noticed.

But there remains the great question of the arrangement

of the Canon. That the order of the prayers that make up

the Canon is a cardinal difficulty is admitted by every

one. The old attempts to justify their present order by

symbolic or mystic reasons have now been given up. The

Roman Canon as it stands is recognized as a problem of

great difficulty. It differs fundamentally from the Anaphora

of any Eastern rite and from the Gallican Canon. Whereas

in the Antiochene family of liturgies (including that of

Gaul) the great Intercession follows the Consecration,

which comes at once after the Sanctus, and in the Alexandrine

class the Intercession is said during what we should call

the Preface before the Sanctus, in the Roman Rite the Intercession

is scattered throughout the Canon, partly before and partly

after the Consecration. We may add to this the other difficulty,

the omission at Rome of any kind of clear Invocation of

the Holy Ghost (Epiklesis). Scholars theorize that the

Roman Mass, starting from the primitive vaguer rite (practically

that of the Apostolic Constitutions), at first followed

the development of Jerusalem-Antioch, and was for a time

very similar to the Liturgy of St. James. Then it was recast

to bring if nearer to Alexandria. This change was made

probably by Gelasius I under the influence of his guest,

John Talaia of Alexandria.

At Rome the Eucharistic prayer

was fundamentally changed and recast at some uncertain

period between the fourth and the sixth and seventh centuries.

During the same time the prayers of the faithful before

the Offertory disappeared, the kiss of peace was transferred

to after the Consecration, and the Epiklesis was omitted

or mutilated into our "Supplices" prayer.

Of the various theories suggested to account for this it

seems reasonable to say with Rauschen: "Although the

question is by no means decided, nevertheless there is

so much in favor of Drew's theory that for the present

it must be considered the right one. We must then admit

that between the years 400 and 500 a great transformation

was made in the Roman Canon".

From the Seventh Century to Modern Times

After Gregory the Great (590-604)

it is comparatively easy to follow the history of the

Mass in the Roman Rite. We have now as documents first

the three well-known sacramentaries. The oldest, called

Leonine, exists in a seventh-century manuscript. Its

composition is ascribed variously to the fifth, sixth,

or seventh century. It is a fragment, wanting the Canon,

but, as far as it goes, represents the Mass we know (without

the later Gallican additions). Many of its collects,

secrets, post-communions, and prefaces are still in use.

The Gelasian book was written in the sixth, seventh,

or eighth century (ibid.); it is partly gallicized

and was composed in the Frankish Kingdom. Here we have

our Canon word for word. The third sacramentary, called

Gregorian, is apparently the book sent by Pope Adrian I

to Charlemagne probably between 781 and 791 (ibid.). It

contains additional Masses since Gregory's time and a set

of supplements gradually incorporated into the original

book, giving Frankish (i.e. older Roman and Gallican) additions.

Dom Suitbert Bäumer and Mr. Edmund Bishop explain

the development of the Roman Rite from the ninth to the

eleventh century in this way: The (pure) Roman Sacramentary

sent by Adrian to Charlemagne was ordered by the king to

be used alone throughout the Frankish Kingdom. But the

people were attached to their old use, which was partly

Roman (Gelasian) and partly Gallican. So when the Gregorian

book was copied they (notably Alcuin d. 804) added to it

these Frankish supplements. Gradually the supplements became

incorporated into the original book. So composed it came

back to Rome (through the influence of the Carlovingian

emperors) and became the "use of the Roman Church".

The "Missale Romanum Lateranense" of the eleventh

century shows this fused rite complete as the only one

in use at Rome. The Roman Mass has thus gone through this

last change since Gregory the Great, a partial fusion with

Gallican elements. According to Bäumer and Bishop

the Gallican influence is noticeable chiefly in the variations

for the course of the year. Their view is that Gregory

had given the Mass more uniformity (since the time of the

Leonine book), had brought it rather to the model of the

unchanging Eastern liturgies. Its present variety for different

days and seasons came back again with the mixed books later.

Gallican influence is also seen in many dramatic and symbolic

ceremonies foreign to the stern pure Roman Rite. Such ceremonies

are the blessing of candles, ashes, palms, much of the

Holy Week ritual, etc.

The Roman Ordines, of which twelve

were published by Mabillon in his "Museum Italicum" (others since by De

Rossi and Duchesne), are valuable sources that supplement

the sacramentaries. They are descriptions of ceremonial

without the prayers (like the "Cærimoniale Episcoporum"),

and extend from the eighth to the fourteenth or fifteenth

centuries. The first (eighth century) and second (based

on the first, with Frankish additions) are the most important.

From these and the sacramentaries we can reconstruct the

Mass at Rome in the eighth or ninth century. There were

as yet no preparatory prayers said before the altar. The

pope, attended by a great retinue of deacons, subdeacons,

acolytes, and singers, entered while the Introit psalm

was sung. After a prostration the Kyrie eleison was sung,

as now with nine invocations; any other litany had disappeared.

The Gloria followed on feasts. The pope sang the prayer

of the day, two or three lessons followed, Interspersed

with psalms. The prayers of the faithful had gone, leaving

only the one word Oremus as a fragment. The people brought

up the bread and wine while the Offertory psalm was sung;

the gifts were arranged on the altar by the deacons. The

Secret was said (at that time the only Offertory prayer)

after the pope had washed his hands. The Preface, Sanctus,

and all the Canon followed as now. A reference to the fruits

of the earth led to the words "per quem hæc

omnia" etc. Then came the Lord's Prayer, the Fraction

with a complicated ceremony, the kiss of peace, the Agnus

Dei (since Pope Sergius, 687-701), the Communion under

both kinds, during which the Communion psalm was sung,

the Post-Communion prayer, the dismissal, and the procession

back to the sacristy (for a more detailed account see C.

Atchley, "Ordo Romanus Primus", London, 1905;

Duchesne, "Origines du Culte chrétien",

vi).

It has been explained how this

(mixed) Roman Rite gradually drove out the Gallican Use.

By about the tenth or eleventh century the Roman Mass

was practically the only one in use in the West. Then

a few additions (none of them very important) were made

to the Mass at different times. The Nicene Creed is an

importation from Constantinople. It is said that in 1014

Emperor Henry II (1002-24) persuaded Pope Benedict VIII

(1012-24) to add it after the Gospel (Berno of Reichenau, "De

quibusdam rebus ad Missæ offic, pertin.",

ii), It had already been adopted in Spain, Gaul, and Germany.

All the present ritual and the prayers said by the celebrant

at the Offertory were introduced from France about the

thirteenth century; before that the secrets were the only

Offertory prayers. There was considerable variety as to

these prayers throughout the Middle Ages until the revised

Missal of Pius V (1570). The incensing of persons and things

is again due to Gallican influence; It was not adopted

at Rome till the eleventh or twelfth century. Before that

time incense was burned only during processions. The three

prayers said by the celebrant before his communion are

private devotions introduced gradually into the official

text. Durandus mentions the first (for peace); the Sarum

Rite had instead another prayer addressed to God the Father.

Micrologus mentions only the second, but says that many

other private prayers were said at this place (xviii).

Here too there was great diversity through the Middle Ages

till Pius V's Missal. The latest additions to the Mass

are its present beginning and end. The psalm "Iudica

me", the Confession, and the other prayers said at

the foot of the altar, are all part of the celebrant's

preparation, once said (with many other psalms and prayers)

in the sacristy, as the "Præparatio ad Missam" in

the Missal now is. There was great diversity as to this

preparation till Pius V established our modern rule of

saying so much only before the altar. In the same way all

that follows the "Ite missa est" is an afterthought,

part of the thanksgiving, not formally admitted till Pius

V.

We have thus accounted for all the elements of the Mass.

The next stage of its development is the growth of numerous

local varieties of the Roman Mass in the Middle Ages. These

medieval rites are simply exuberant local modifications

of the old Roman rite. The same applies to the particular

uses of various religious orders (Carthusians, Dominicans,

Carmelites etc.). None of these deserves to be called even

a derived rite; their changes are only ornate additions

and amplifications; though certain special points, such

as the Dominican preparation of the offering before the

Mass begins, represent more Gallican influence. The Milanese

and Mozarabic liturgies stand on quite a different footing;

they are the descendants of a really different rite --

the original Gallican -- though they too have been considerably

Romanized.

Meanwhile the Mass was developing

in other ways also. During the first centuries it had

been a common custom for a number of priests to concelebrate;

standing around their bishop, they joined in his prayers

and consecrated the oblation with him. This is still

common in the Eastern rites. In the West it had become

rare by the thirteenth century. St. Thomas Aquinas (d.

1274) discusses the question, "Whether

several priests can consecrate one and the same host" (Summa

Theol., III, Q. lxxxii, a. 2). He answers of course that

they can, but quotes as an example only the case of ordination.

In this case only has the practice been preserved. At the

ordination of priests and bishops all the ordained concelebrate

with the ordainer. In other cases concelebration was in

the early Middle Ages replaced by separate private celebrations.

No doubt the custom of offering each Mass for a special

intention helped to bring about this change. The separate

celebrations then involved the building of many altars

in one church and the reduction of the ritual to the simplest

possible form. The deacon and subdeacon were in this case

dispensed with; the celebrant took their part as well as

his own. One server took the part of the choir and of all

the other ministers, everything was said instead of being

sung, the incense and kiss of peace were omitted. So we

have the well-known rite of low Mass (missa privata). This

then reacted on high Mass (missa solemnis), so that at

high Mass too the celebrant himself recites everything,

even though it be also sung by the deacon, subdeacon, or

choir.

The custom of the intention of

the Mass further led to Mass being said every day by

each priest. But this has by no means been uniformly

carried out. On the one hand, we hear of an abuse of

the same priest saying Mass several times in the day,

which medieval councils constantly forbid. Again, many

most pious priests did not celebrate daily. Bossuet (d.

1704), for instance, said Mass only on Sundays, Feasts,

every day in Lent, and at other times when a special

ferial Mass is provided in the Missal. There is still

no obligation for a priest to celebrate daily, though

the custom is now very common. The Council of Trent desired

that priests should celebrate at least on Sundays and solemn

feasts (Sess. XXIII, cap. xiv). Celebration with no assistants

at all (missa solitaria) has continually been forbidden,

as by the Synod of Mainz in 813. Another abuse was the

missa bifaciata or trifaciata, in which the celebrant said

the first part, from the Introit to the Preface, several

times over and then joined to all one Canon, in order to

satisfy several intentions. This too was forbidden by medieval

councils (Durandus, "Rationale", IV, i, 22).

The missa sicca (dry Mass) was a common form of devotion

used for funerals or marriages in the afternoon, when a

real Mass could not be said. It consisted of all the Mass

except the Offertory, Consecration and Communion (Durandus,

ibid., 23). The missa nautica and missa venatoria, said

at sea in rough weather and for hunters in a hurry, were

kinds of dry Masses. In some monasteries each priest was

obliged to say a dry Mass after the real (conventual) Mass.

Cardinal Bona (Rerum liturg. libr. duo, I, xv) argues against

the practice of saying dry Masses. Since the reform of

Pius V it has gradually disappeared. The Mass of the Presanctified

is a very old custom described by the Quinisext Council

(Second Trullan Synod, 692). It is a Service (not really

a Mass at all) of Communion from an oblation consecrated

at a previous Mass and reserved. It is used in the Byzantine

Church on the week-days of Lent (except Saturdays); in

the Roman Rite only on Good Friday. |